Beginning Jan. 1, 2023, if you’re one of an estimated 76,000 owners who lives or operates in California with a pre-2010 emissions-spec engine, your ability to operate in the state will be in jeopardy.

Nearly 10 years ago, the California Air Resources Board’s Truck and Bus Regulation banned the use of all trucks powered by 2006 and older emissions-spec engines, with some narrow exceptions, and beginning in 2023, the rule, along with the similar Drayage Rule for dray operators, takes vehicle bans a step further. If the deadline stands as currently written in the rule, use of all 2007-2009-emissions-spec engines will be prohibited.

Part of CARB’s enforcement mechanism this go-around is to prevent registration or renewal of any such vehicle — the default CARB and the California Department of Motor Vehicles will use in that regard is an assumption that truck model years 2008 through 2010 are powered by by 2007-2009 engines. Unless owners take steps with the agencies to prove otherwise, registrations/renewals will be blocked.

Given high interest in 2010-emissions-spec tech at the time of that generation of engines’ introduction, it’s likely that many owners of 2010 model year trucks do in fact include 2010-emissions-spec engines (featuring diesel exhaust fluid dosing in selective catalytic reduction systems).

Drivers who do own a 2010 model year truck with a 2010 model year engine can report that their engine is compliant through CARB’sExcluded Diesel Vehicle Reporting data base (EDVR). The owner will be required to upload photos of the engine compartment that still shows part of the truck’s exterior, as well as a photo of the Emission Control Label. CARB suggests that this information be submitted “well in advance of your registration due date” to minimize the possibility of registration delays.

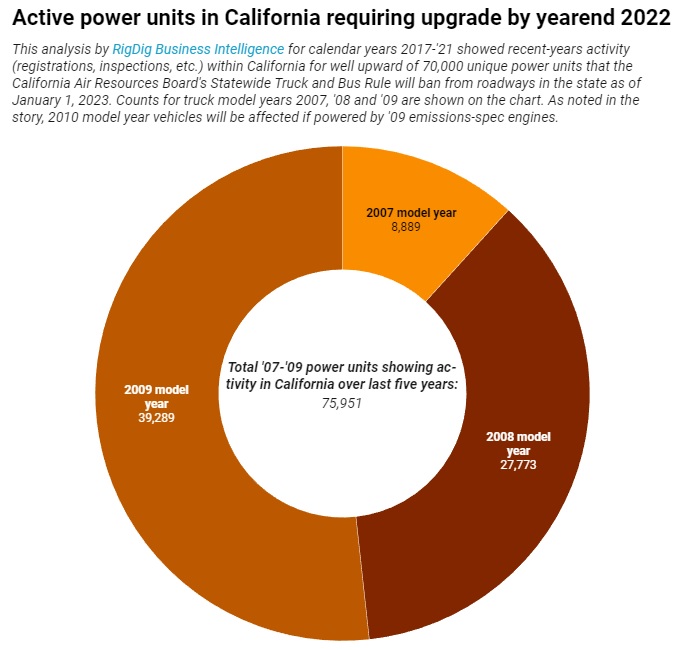

An analysis from Overdrive sister company RigDig Business Intelligence found 75,951 unique VINs for 2007-2009 model year trucks with some level of activity in California over the last five years, including registrations and inspections.

For owners domiciled in California, these trucks will be blocked from registering by the California Department of Motor Vehicles after Jan. 1. Out-of-state owners operating these older engines will run the risk of hefty fines and even the possibility of the truck being impounded.

Joe Rajkovacz, director of governmental affairs and communications with the Western States Trucking Association, said some out-of-state operators whose trucks are already out of compliance with the rule may have been able to get in and out of the state without any problems, but he said it’s really like “throwing the dice.”

Next year, once all of the California-domiciled trucks that don’t comply are blocked from registering, enforcement personnel will no longer have to focus on those trucks, Rajkovacz said. The state will then “be able to redeploy their inspectors to the state’s ports of entry,” he added, which will make it more difficult for out-of-state operators to evade the rule. CARB’s low-use exemption for older rigs running fewer than 1,000 miles annually in the state is still available, however, for out-of-state and in-state operators, with a variety of miles tracking/reporting requirements. Read more about it via the CARB explainer at this link. The mileage limitation was reduced from 5,000 miles in 2018 after CARB lost a legal appeal challenging it and other compliance alternatives.

There have been recent efforts by a number of trucking groups — including the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, American Trucking Associations, Truckload Carriers Association, WSTA and more — to get CARB to delay the implementation of the final phase of the rule due to manufacturing challenges causing shortages of both new and used trucks.

Rajkovacz said there have been discussions about extending the final compliance date, but the groups have not yet received a response from CARB on a March 11 letter requesting the regulatory relief.

Rajkovacz sought to make clear that the request to delay the final compliance date “is not an attack on the final rule,” he said, but when the rule was finalized 13-14 years ago, no one could have predicted the truck market would be in its current situation as the final phase of the rule was set to take effect, to say nothing of supply chain issues associated with West Coast and other port congestion extending well into the U.S. interior through much of the last year to the present day.

“We shall see if there’s pragmatism,” Rajkovacz said. “The impact of taking 80,000 trucks out of the supply chain — that’s about 17% of California’s commercial motor vehicle fleet.”

David Arsenault is President of GSC Logistics, involved in drayage operations, transloading and intermodal chassis provisioning for, he estimated, 20% of import volumes in California. When he spoke as part of a port-congestion-focused seminar at the Truckload 2022 conference of the Truckload Carriers Association in Las Vegas two weeks ago, he illustrated some easing of congestion in West Coast ports, though there’s not necessarily been a “miraculous improvement in productivity,” he said.

“A high of 109 ships back on January 9” on their way to unload at Los Angeles/Long Beach, Arsenault noted, had been reduced to 46 as of that late-March week, a good bit of the reduction coming by way of the Chinese Lunar New Year and time off across the Pacific. At Oakland, the count was 20, he said, though ports had shifted their rules to prioritize ships for unload not at anchor point but from the minute they sail. “If you fly in over L.A./Long Beach, you don’t see ships at anchor. The problem got pushed out over the anchor” to the high seas.

In the coming implementation of the Truck and Bus and Drayage rules, he anticipates the sound of “the next shot heard round the world” when it comes to potential drags on California ports’ efficiency. He estimated 6,000 trucks in Southern California, and another 1,800 or more in Northern California, “will no longer have access to a marine terminal” as of January 1, 2023, if compliance delays don’t see the light of day. That represents as much as a “third of the drayage fleet. … This will really exacerbate” the problem of port congestion “in a significant way in California.”

Said Rajkovacz, “If you think there’s been a supply chain issue before, you ain’t seen nothing yet if there’s not some pragmatism within the government of California.”

Delays on the production of new vehicles, meanwhile, have “really spiked the used-market prices up,” Arsenault noted, and as anyOverdrive reader well knows, even well before “this regs threshold goes into play. If anybody’s looking to sell about 100 tractors, I’m in the market for them.” –Todd Dills contributed to this report.